This is an archived website, available until June 2027. We hope it will inspire people to continue to care for and protect the South West Peak area and other landscapes. Although the South West Peak Landscape Partnership ended in June 2022, the area is within the Peak District National Park. Enquiries can be made to customer.service@peakdistrict.gov.uk

The 5-year South West Peak Landscape Partnership, 2017-2022, was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Revealing Errwood Hall: the story behind the Errwood Hall Revealed app

Posted on 14 July 2022

Catherine Parker Heath, cultural heritage officer for the South West Peak Landscape Partnership, together with SWP volunteers and local enthusiasts have created content for a multi-media augmented reality app, working with digital media company, Bloc Digital. The result is 'Errwood Hall Revealed'.

Catherine Parker Heath, cultural heritage officer for the South West Peak Landscape Partnership, together with SWP volunteers and local enthusiasts have created content for a multi-media augmented reality app, working with digital media company, Bloc Digital. The result is 'Errwood Hall Revealed'.

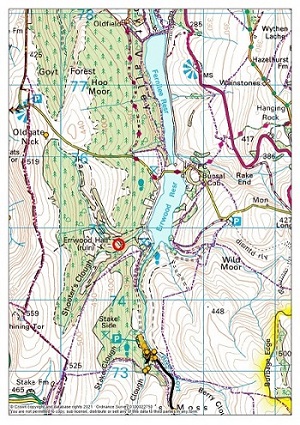

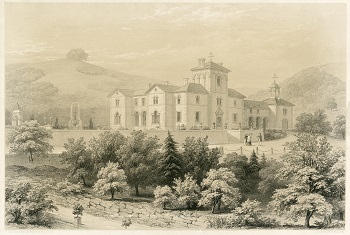

The isolated ruins of Errwood Hall lie in the picturesque Goyt Valley (see map).

Built in the 1840s by Samuel Grimshawe II, Errwood Hall was once a magnificent country home.

Grimshawe was a wealthy Victorian industrialist who unfortunately did not live very long to appreciate his achievement (he died in 1851).

The hall was then lived in by Grimshawe II's son Samuel Grimshawe III, along with his wife Jessie and family.

Subsequently, the hall was bought by Stockport Corporation in 1930, on the death of Mary, who was Samuel and Jessie’s daughter. She was the last of the family line.

The hall was purchased along with much of the valley and surrounding area, to make way for the two reservoirs that can be seen today – Fernilee (built in 1938) and Errwood (built in 1967).

The grand house had been a family home for less than 100 years.

The grand house had been a family home for less than 100 years.

Today, the area is owned by United Utilities and managed by Forestry England.

![]() Crichton Porteous, a local author, once wrote in his Peakland book of 1954, “And none who see what is there now can form any proper idea of the beautiful old home”.

Crichton Porteous, a local author, once wrote in his Peakland book of 1954, “And none who see what is there now can form any proper idea of the beautiful old home”.

It is easy to see why he might say such a thing when looking at the ruined remains.

Many old photos of the hall in its heyday exist, but when standing at the ruins without such photographs to hand, it can be hard to imagine how the hall actually looked with any accuracy.

As part of the South West Peak Landscape Partnership’s legacy, the aim was to create a novel way for existing audiences to engage with Errwood Hall and entice new audiences to appreciate it in a way that would last for years to come.

As part of the South West Peak Landscape Partnership’s legacy, the aim was to create a novel way for existing audiences to engage with Errwood Hall and entice new audiences to appreciate it in a way that would last for years to come.

These new audiences were to include young people, schoolchildren, and those who could not physically access the site for a variety of reasons.

This meant we wanted something that could be used off-site that was not a website (especially as there is already a fantastic website in place www.goyt-valley.org.uk).

We wanted the new 'something' to be used on-site without the physical kind of interpretation board that so often detracts from or interrupts the settings of heritage sites.

We knew that one thing visitors to the ruins of the hall appreciate is its isolated nature. It is an evocative romantic ruin.

What could possibly do all of these things?

The answer, of course was an app, tapping into the technological world that has become part the daily lives of most of us.

Apps can do almost anything it seems, and one path we wanted to explore was augmented reality.

The dream was to have a full reconstruction of the hall inside and out.

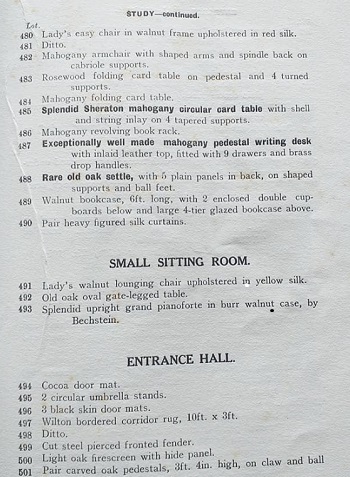

We imagined being able to walk through the ruins of the building and actually see the paintings on the walls and the furniture in place as had been described by visitors to the house in its heyday and as listed in the sale catalogue of 1930 (pictured here).

But could it be done?

Could the hall be recreated as it once looked so people on-site and off-site could appreciate its past grandeur?

The answer was of course yes!

But (it seems there is always a ‘but’), achieving our aim depended on a number of factors, such as budget, timescale, the information to hand, and the nature of the site itself in terms of connectivity, signal and terrain.

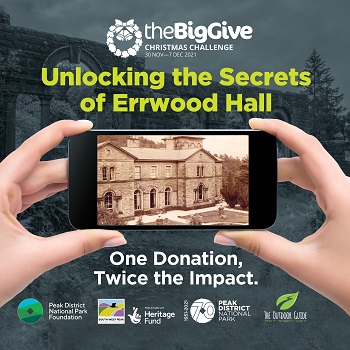

The project needed funding and it was championed by The Big Give in November 2021, and the Peak District National Park Foundation and many members of the public kindly donated.

The project needed funding and it was championed by The Big Give in November 2021, and the Peak District National Park Foundation and many members of the public kindly donated.

There were also generous donations from The Outdoor Guide in memory of a friend and colleague Liz MacKenzie who died in 2021, and donations from Mr James Butler in memory of his grandparents and from the Bingham Trust.

The campaign was a great success, and we reached the target of £5000.

However, apps can be expensive to make, especially those needing 3D models and augmented reality capabilities.

They also need time to be made and, with the South West Peak Landscape Partnership ending in June 2022, time was most definitely limited.

There was also very few photos of the interior of the house to put into an app.

The location of the site also posed some challenges. Whilst the signal can be good for some mobile phone providers it is not for all and is not consistent across the site, and the physical obstacles of the ruins on the ground meant that we had to be aware of health and safety considerations of people walking around looking though phones and tablets and tripping.

All of this meant that the team needed to be realistic about what could be achieved – for now at least.

However, the fundamentals of what was wanted at the outset, could still most definitely be created: there could be an app that could work off-site as well as on-site; research and knowledge could be presented to users through the written word, images and sound; people would be able to see and appreciate the grandeur and scale of the hall as it once was; and it could be ensured that people understood the ruins as they are today and their place in a working and managed landscape.

The first step was to understand how the hall had once looked. This part was thought to be relatively easy.

The first step was to understand how the hall had once looked. This part was thought to be relatively easy.

There are photos of the hall from its heyday years and the belief was that the plans for the hall drawn by architect Alexander Roos did exist and some of the team believed they had indeed seen these.

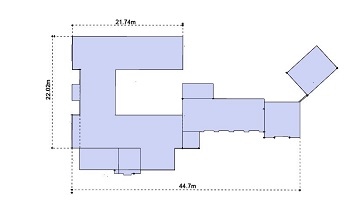

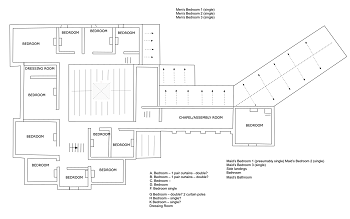

There was already an existing 3D model of the hall too created by David Easton of Furness Vale Local History Society.

And, Peak District National Park volunteer rangers had a layout drawn up for a Family Day they organised some years ago.

However, as research began, it became apparent that there were not any original floorplans that could be used, and those layouts that were in existence were actually informed guesses based on the ruins that can be seen on the ground today.

However, as research began, it became apparent that there were not any original floorplans that could be used, and those layouts that were in existence were actually informed guesses based on the ruins that can be seen on the ground today.

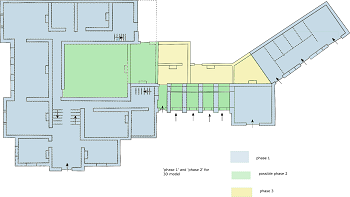

Here is a link to David Easton’s model on Sketchup and the floor plan based on this is pictured here.

David, perhaps sensibly, steered clear of naming individual rooms. However, the volunteer rangers were brave enough to name some of the rooms.

After coming to various dead ends regarding original plans, there was one last hope.

It was common knowledge that Errwood Hall had become a Youth Hostel for a few years after the death of Mary Grimshawe in 1930.

It was common knowledge that Errwood Hall had become a Youth Hostel for a few years after the death of Mary Grimshawe in 1930.

With great anticipation, one volunteer, Angela, got in touch with the YHA. Unfortunately, all hopes were dashed when the YHA archivist replied that the Hall had never been a youth hostel – this had been at Errwood Farm some distance to the northwest of the grand house.

So no original plan, but at least a misplaced belief could be corrected.

Up until this point, it had been assumed that there had been an internal courtyard.

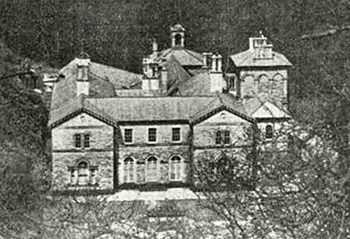

All the existing layouts showed this and the ruins on the ground certainly suggest it. The vertical view of the ruins, pictured here, (photograph courtesy of Richard Knisely Marpole) shows this.

However, the existence of the courtyard began to be questioned.

Although the hall was dismantled in 1934 and much of the best stone sold on, the site was basically mounds of rubble until it was levelled, consolidated, and made safe in the 1980s.

But, there was no way of knowing how accurately this levelling and subsequent divisions of ‘rooms’ had been.

It is quite clear to see that the internal surface level of the hall is significantly higher than it was originally.

In fact, the floor of the stables is the only original, intact surface to still remain (seen bottom right in the photograph above).

The existence of the courtyard was discussed many times, and it seemed possible to find evidence to support conflicting views.

One photograph convinced many that there must have been a courtyard.

One photograph convinced many that there must have been a courtyard.

Yet in reality, a courtyard could not actually be seen, only the absence of roof at the same height as the others.

In fact, further study determined that the photograph may very well have been taken after demolition began. Although the image quality was not very good, the windows looked as if they were missing and rooms behind were empty shells.

On the other hand, another photo (which is shown here), whilst also suggesting a courtyard, convinced others that there certainly was not one.

Look closely and you can see that there could have been pitched roofs across the central area at first floor level.

However, the most convincing pieces of evidence for there being no courtyard, were historic maps.

The 25-inch OS map from the late 19th century clearly shows Errwood Hall as a solid block, as you can see in the extract here.

Maps of other halls that do have courtyards, clearly show the courtyards.

In comparison, look at the 1896 map of Lyme Park, which is not far away from Errwood Hall (see map below).

The inner courtyard at Lyme Park is clearly drawn as a rectangle within the walls of the house.

These historic maps, whilst they are representations of what was on the ground, are known to be very accurate.

It was considered that such an important detail would not be something the mapmakers would have got wrong at Errwood Hall.

In addition, the description of the house by the reporter, the list of rooms in the sale catalogue, along with description of a servants’ hall in the basement, as well as being extensive, all strongly suggested there would not have been room for a courtyard.

Space is limited on the terrace that was created for the hall, why waste it by having a courtyard?

Moreover, not one of these contemporary descriptions even mention its existence.

There was another possibility to consider too, what if the roof was flat instead of sloping?

Research into other houses of similar age and type was carried out and many incorporated rooms with flat roofs, perhaps with skylights, that were surrounded by pitched roofs.

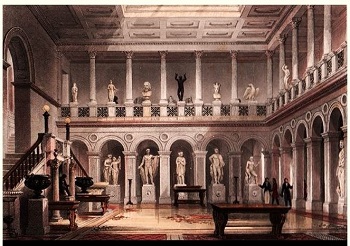

One house, Deepdene, sadly no longer standing, which was also designed by Alexander Roos, the architect for Errwood Hall, had an internal room, with a flat roof and skylight.

One house, Deepdene, sadly no longer standing, which was also designed by Alexander Roos, the architect for Errwood Hall, had an internal room, with a flat roof and skylight.

The picture shown here is from The DiCaillo Campanion Ltd. (https://www.thedicamillo.com/house/deepdene-the-deepdene/) and shows perhaps what the central room could possibly have been like at Errwood. Could it have been a grand space to show the family's collections? A space for dancing when parties were held? Or was it the billiard room?

Eventually, there was agreement that there had been no courtyard at Errwood Hall.

If only someone had though to take a photograph of the rear of the house before it was demolished!

There then followed the task of working out which rooms would have been where.

There then followed the task of working out which rooms would have been where.

The 1930s sale catalogue was used to try to place them all.

It was thought, again, that this would be relatively straight forward, with rooms being listed in order, but it did not quite turn out like this.

Different versions were tried and the number of question marks on this layout show the uncertainty, but there was no way of knowing with any certainty which version was right.

It is also important to remember that the function of rooms can change over time.

Taking the sale catalogue room by room, you can see in the extract pictured, it starts with the study, then the sitting room, then the entrance hall, suggesting that the study and small sitting room were on either side of the main entrance before coming into the entrance hall proper.

Incidentally, the study was described as having one pair of curtains, but the sitting room had no curtains listed. If the mention of pairs of curtains were to be taken as indicating number of windows, what did this mean?

Well, in this case, it is clear that numbers of curtains could not be directly related to numbers of windows.

The sale catalogue mentions the entrance hall and followed by the library, with three pairs of curtains. This immediately suggested that the library must have been the room with the three French windows looking out onto the garden – surely?

However, placing it here seemed to cause more difficulties then it solved and it could not be certain that these curtains could not have been brought from other rooms for the purpose of the sale.

There is nothing else listed in the sale catalogue as being in the library, although the books are listed elsewhere in the catalogue.

Contact was made with author Trevor Yorke, who had written many books on country houses and houses throughout the ages. He suggested that the large room with the three French windows onto the garden would most likely have been the drawing room. This perhaps meant the order of the sale catalogue could still be followed and the library would be the next room along listed after the entrance hall.

Then there was the billiard room. Attempts to solve this and other queries involved working out how big a ¾ size billiard table would be, which was listed in the sale catalogue, and seeing how that would fit in the rooms.

Rugs listed were also measured out.

It was understood that the kitchens would be near the scullery and the butler’s pantry, which too would be relatively close to the dining room, but how could all this fit together?

There were stories of parties, where food was set out on the billiard table and then where people would head to the servants’ hall in the basement for dancing.

There were stories too of extensive wine cellars. It seemed impossible to come to any definite conclusion.

When it came to the first floor and second floor, the mystery increased.

When it came to the first floor and second floor, the mystery increased.

There were so many bedrooms!

The windows were closely observed and attempts were made to divide the space.

Chimneys too were looked at, but again there seemed no way of deciding with any certainty.

There seemed to be lots of information but it also felt like trying to do a jigsaw without any of the pieces!

It appeared to be an impossible task to decide on the layout with any certainty, all there is are different versions from which we can pick the one we like the best…

An attempt was made at working out what could have been possible phases of the house, with the long extension (including the three arches on the right) being once open, as suggested by the architect’s drawings (courtesy of Buxton Museum), and perhaps only later blocked and windows installed.

An attempt was made at working out what could have been possible phases of the house, with the long extension (including the three arches on the right) being once open, as suggested by the architect’s drawings (courtesy of Buxton Museum), and perhaps only later blocked and windows installed.

The extension too would have been narrower than suggested by the remains on the ground and the existing layouts.

This could be worked out from looking very carefully at the rooflines in the old photographs.

Looking at the rooflines, and chimneys seemed to also confirm, the belief in a central room and no courtyard.

The rooms at the back of the extension – if the remains on the ground can be believed – would have been later additions.

The rooms at the back of the extension – if the remains on the ground can be believed – would have been later additions.

Perhaps the kitchens would have at first been at the back of the main house and then later moved here?

All that we are left with are possibilities and probabilities, and very few definitely-s.

But this in many ways is the appeal of archaeology and history, and it has to be embraced. It is important to acknowledge uncertainty. New evidence brought to light can always change the picture.

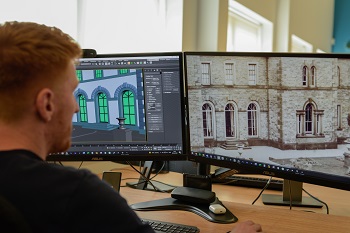

However, for the app, decisions had to be made in order for app developers to recreate the hall as a 3D model.

This was decided by taking a vote that meant the reconstruction 3D model would be based on phase 1 and a possible phase 2 on this plan.

This was decided by taking a vote that meant the reconstruction 3D model would be based on phase 1 and a possible phase 2 on this plan.

Other difficult decisions had to be made also.

With regards to recreating the interior, the fact there was a lack of images, and the time needed to recreate interiors from descriptions, the lack of time we had and the expense of this, meant that only the exterior of the hall could be reconstructed.

But we could have a number of fact files and the inclusion of sounds files.

Therefore, the app developers set about their task, creating the model, looking closely at the photographs and layouts they had been given.

Therefore, the app developers set about their task, creating the model, looking closely at the photographs and layouts they had been given.

New research and research that others had done before was brought together, fact files were written, and sound files were recorded, making the app hopefully increasingly appealing.

The fact files are themed around the mystery of the layout, life at the hall, the people of the hall and the area today and how it is managed by Forestry England and United Utilities.

There are six sound files that are associated with the fact files, allowing in most cases voices of the past to come to life.

There is the voice of the journalist who visited in 1883, a letter read by Ann Bailey that she sent to her mother in 1895 and the journalist account in a Macclesfield newspaper about a party lasting until 4 in the morning. It was not the only one. There is the voice of a man, John, who had worked on the Estate all his life until a new bailiff came along, which he did not like.

A number of people lent their voices: Philip Holland, researcher and ‘custodian’ of the Derbyshire dialect, poet, and retired local farmer, and father of Elizabeth (Liz) Mackenzie; Robbie Carnegie, of Buxton Drama League; Chris Wilman who is tireless in her pursuit of uncovering secrets of the past; David Stirling, creator of the www.goyt-valley.org.uk website; and Shirley Miller, wife of David Miller, who kindly offered her services.

As was intended from the outset, the app can be used off-site and on-site.

This app really comes into its own in its use off-site.

The 3D reconstruction of Errwood Hall can be placed ‘model-sized’ on your kitchen table! In schools, the 3D model can be placed on tables in the class room and then looked at more closely.

More excitingly, it could be placed life-size on a playing field or playground.

There are hopes for the future. How else and where else can this technology be used? There is so much potential.

There is certainly more that could be done with the Errwood Hall App, but this will have to wait until more funding can be found.

The app could be expanded, and geolocations could be placed on-site to match the 3D model to the ruins exactly – although these would have to be discrete – possibly footprints in stone embedded into the ground to show where people would need to stand to launch the app to locate it. All the internal rooms could be created and dressed according to the descriptions, taking the time to work out and making educated guesses as to where things would be.

The app could be expanded, and geolocations could be placed on-site to match the 3D model to the ruins exactly – although these would have to be discrete – possibly footprints in stone embedded into the ground to show where people would need to stand to launch the app to locate it. All the internal rooms could be created and dressed according to the descriptions, taking the time to work out and making educated guesses as to where things would be.

What was wanted more than anything is an app that can engage all kinds of people: those who know about the hall, those who are coming to it for the first time; those who are stood there on site and those who cannot, or perhaps no longer visit in person; young people in schools, young people in their own time, who are familiar with this kind of technology and people who have never downloaded an app before; people here as visitors perhaps on holiday, those who live in the area, those who live on the other side of the world - all kinds of people. And hopefully this app will do those things.

This could be just the beginning.

The app is free and available to download on the App Store and Google Play. Type in Errwood Hall Revealed and follow the prompts to install and download.

(The historic photographs used on this page are from the Gerald Hancock Collection, courtesy of David Stirling www.goyt-valley.org.uk unless otherwise stated).